Code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltThis section focuses on using using the SVD to find a linear subspace of lower dimension in which to project the data. The objective is to show that dimensionality reduction works well in linear subspaces when the underlying structure is linear but quickly shows limitation for non-linear structures.

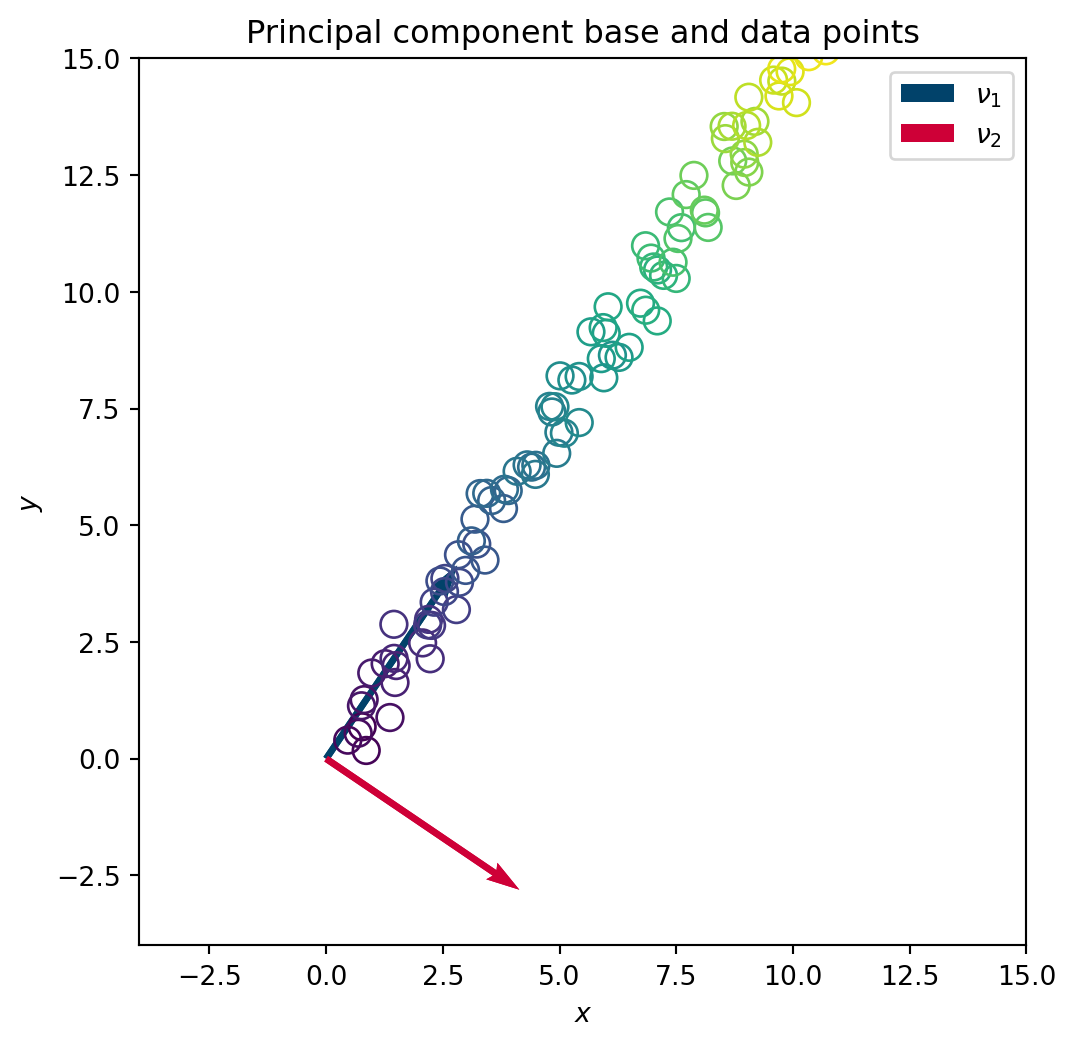

We first apply the SVD to an affine functions. The physical space of the dataset is \(\mathbb{R}^2\) but the data set is in fact 1D. The SVD is used to find a suitable 1D linear subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^2\) in which the data can be projected without loosing any information.

We start by defining the function and by computing the SVD of all the 2D snapshots.

n_sample = 100 # Choose number of samples

x = np.linspace(0,10,n_sample) # create vector x

# Affine parameters

a = 1.5 # Slope

b=0 # y-axis origin

# Affine function

y = a*x+b # Affine function

X = np.stack((x,y)) # Create numpy array

# Noise

n_coef = 1 # Noise magnitude

X += + n_coef*np.random.rand(*X.shape) # Noisy data

# SVD

U,S,V = np.linalg.svd(X) # SV DecompositionTo visualise the underlying space found in the data by the SVD, we plot the principal directions \(\nu_1\) and \(\nu_2\) onto the initial dataset.

colors_1D = plt.cm.viridis(np.linspace(0, 1, len(X[0,:]))) # Generate a color gradient

# plots

# Origin point

origin = np.array([[0, 0], [0, 0]])

U_scaled = -5*U

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

# plt.quiver(*origin, U_scaled[:, 0], U_scaled[:, 1], angles='xy', scale_units='xy', scale=1, color=['r', 'b'])

plt.quiver(*origin, U_scaled[0, 0], U_scaled[0, 1], angles='xy', scale_units='xy', scale=1, color='#01426A', label=r'$\nu_1$')

plt.quiver(*origin, U_scaled[1, 0], U_scaled[1, 1], angles='xy', scale_units='xy', scale=1, color='#CE0037', label=r'$\nu_2$')

plt.legend()

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal')

plt.ylim(-4, 15)

plt.xlim(-4, 15)

plt.xlabel(r"$x$")

plt.ylabel(r"$y$")

# plt.plot(X[0,:],X[1,:],'+')

# plt.scatter(X[0,:],X[1,:], color=colors_1D, s=100)

plt.scatter(X[0,:],X[1,:], facecolors='none', edgecolors=colors_1D, s=100)

plt.title("Principal component base and data points")

plt.show()

plt.close()

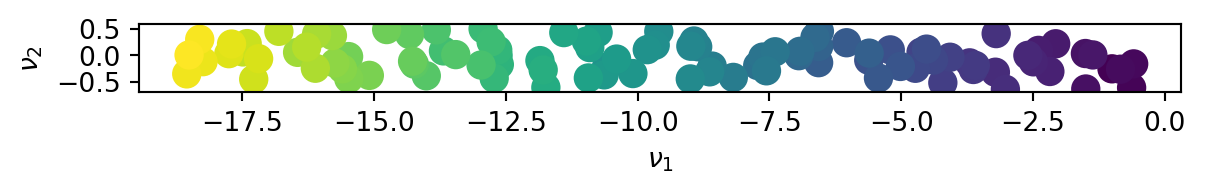

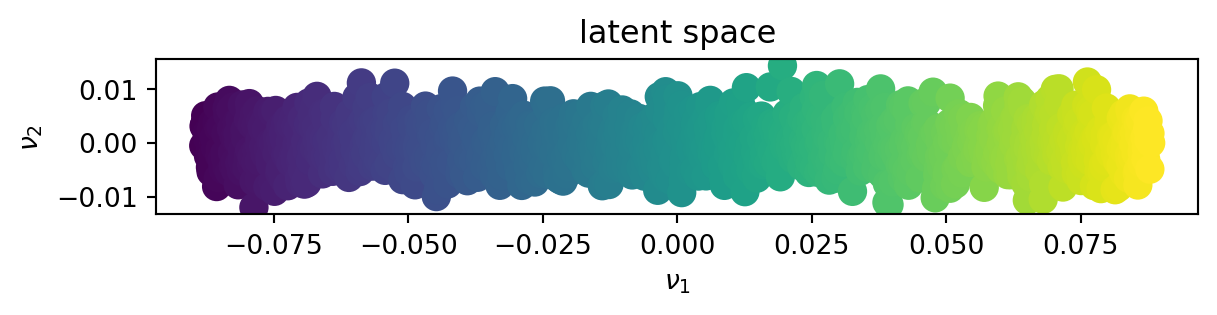

We then project the data onto the latent space \(\left(\nu_1,\nu_2\right)\).

We can see that the initial 2D data in fact lies in a 1D space and that the first principal direction \(\nu_1\) is sufficient to describe the full data set.

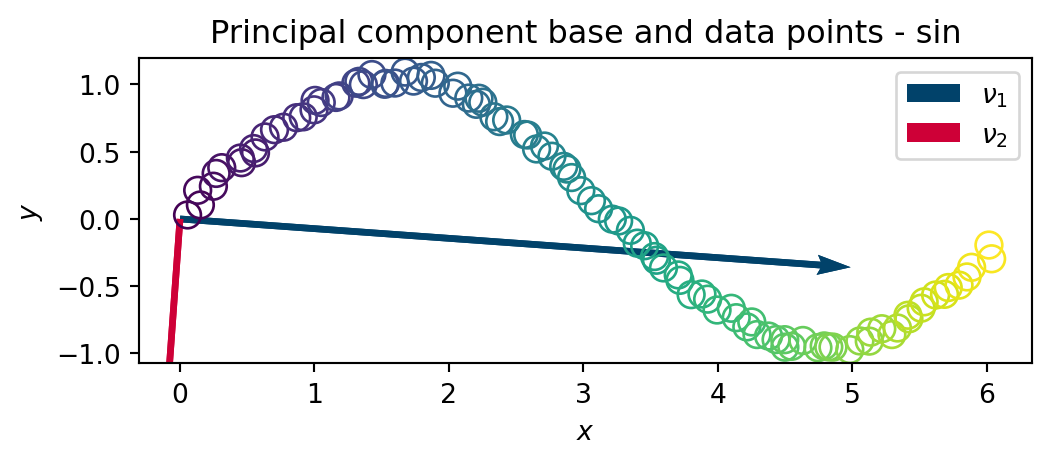

To show the limitation of the SVD to find non-linear manifold, a sin function is now studied in a similar manner.

Again, we start by defining the function and by computing the SVD of all the 2D snapshots.

# In 1D for an sin function

n_sample = 100 # Choose number of samples

# x = np.linspace(0,np.pi/4,n_sample)

x = np.linspace(0,6,n_sample) # create vector x

# Affine parameters

a = 1.5 # Slope

b=0 # y-axis origin

# Affine function

y = np.sin(x) # Sin function

X = np.stack((x,y)) # Create numpy array

# Noise

n_coef = 0.1 # Noise magnitude

X += + n_coef*np.random.rand(*X.shape) # Noisy data

# SVD

U,S,V = np.linalg.svd(X) # SV DecompositionIn a similar manner, we plot the principal directions \(\nu_1\) and \(\nu_2\) onto the data set

# plots

# Origin point

origin = np.array([[0, 0], [0, 0]])

U_scaled = -5*U

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

# plt.quiver(*origin, U_scaled[:, 0], U_scaled[:, 1], angles='xy', scale_units='xy', scale=1, color=['r', 'b'])

plt.quiver(*origin, U_scaled[0, 0], U_scaled[0, 1], angles='xy', scale_units='xy', scale=1, color='#01426A', label=r'$\nu_1$')

plt.quiver(*origin, U_scaled[1, 0], U_scaled[1, 1], angles='xy', scale_units='xy', scale=1, color='#CE0037', label=r'$\nu_2$')

plt.legend()

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal')

# plt.ylim(-4, 15)

# plt.xlim(-4, 15)

plt.xlabel(r"$x$")

plt.ylabel(r"$y$")

# plt.plot(X[0,:],X[1,:],'+')

plt.scatter(X[0,:],X[1,:], facecolors='none', edgecolors=colors_1D, s=100)

plt.title("Principal component base and data points - sin")

plt.show()

plt.close()

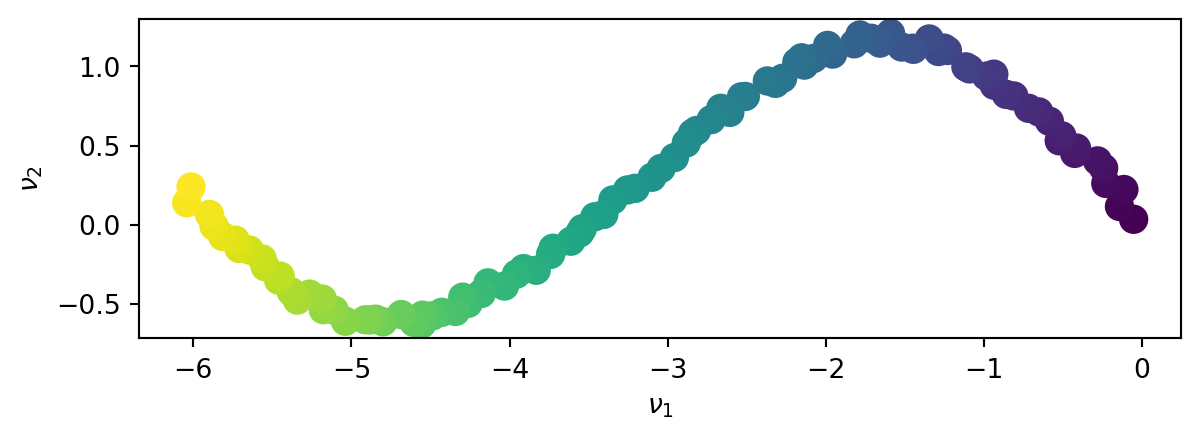

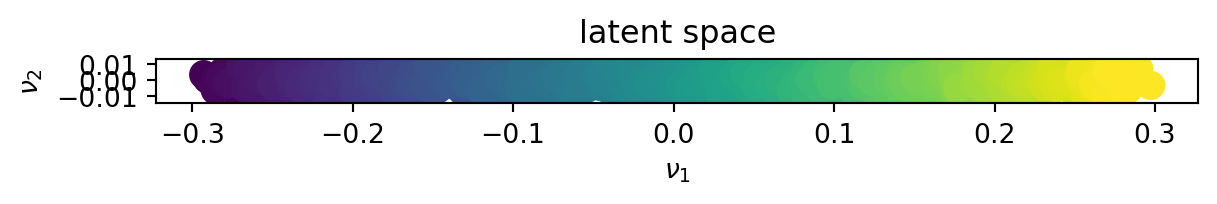

And we project the data onto the latent space \(\left(\nu_1,\nu_2\right)\).

This time, the SVD does not exhibit a lower dimension space in which the data can be represented. Both principal directions are required to represent the non-linear data set.

This section focuses on using using the kPCA to find a non-linear manifold of lower dimension in which to project the data. The objective is to show that dimensionality reduction works well in non-linear cases where the SVD failed.

We first apply the SVD to a sin function. The physical space of the dataset is \(\mathbb{R}3\) but the data set is in fact 2D. The kPCA is used to find a suitable 2D (non-linear) manifold in which the data can be projected without loosing any information.

Note: The PCA conventions are transposed compared to SVD’s conventions

We define the kPCA paramerets, namely

We now compute the kernel matrix based on the distance matrix using a Gaussian kernel

\[K(x_i, x_j) = \exp\left(-\frac{\|x_i - x_j\|^2}{2\sigma^2}\right)\]

We then center the kernel matrix as the PCA expects 0-mean data

\[ K_{\text{centered}} = K - \frac{1}{n} \mathbf{1} K - \frac{1}{n} K \mathbf{1} + \frac{1}{n^2} \mathbf{1} K \mathbf{1} \]

We perform an SVD of the centered kernel to find the principal directions of the high dimensional space,

that we then truncates. we then project the initial dataset onto the principal directions in the latent space

In the physical space (the plot is interactive, feel free to explore the 3D dataset !)

colors = plt.cm.viridis(np.linspace(0, 1, len(X[0,:]))) # Generate a color gradient

import plotly.graph_objects as go

# colors_plotly = colors[:, :3]

colors_plotly = np.linspace(0, 1, X.shape[1])

x_points = X[0, :]

y_points = X[1, :]

z_points = X[2, :]

# Create the 3D scatter plot

fig = go.Figure(data=[go.Scatter3d(

x=x_points,

y=y_points,

z=z_points,

mode='markers',

marker=dict(

size=5, # Size of the markers

color=colors_plotly, # Color of the markers

colorscale='viridis', # Color scale

showscale=True, # Show color scale

)

)])

fig.update_layout(

scene=dict(

xaxis_title='x',

yaxis_title='y',

zaxis_title='z',

),

title='Physical Space'

)

fig.show()In the latent space

We can see that contrary to the SVD, the kPCA could decrease the dimensionnality of the supposidly 3D space into a 2D space, finding the underlying non-linear manifold onto which the dataset lies.

We now apply the SVD to an affine function. The physical space of the dataset is still \(\mathbb{R}3\) but the data set is in fact 2D. The kPCA is used to find a suitable 2D linear subspace similarly to what the SVD would give.

Note: The PCA conventions are transposed compared to SVD’s conventions

We define the kPCA paramerets, namely

We now compute the kernel matrix based on the distance matrix using a Gaussian kernel

\[K(x_i, x_j) = \exp\left(-\frac{\|x_i - x_j\|^2}{2\sigma^2}\right)\]

We then center the kernel matrix as the PCA expects 0-mean data

\[ K_{\text{centered}} = K - \frac{1}{n} \mathbf{1} K - \frac{1}{n} K \mathbf{1} + \frac{1}{n^2} \mathbf{1} K \mathbf{1} \]

We perform an SVD of the centered kernel to find the principal directions of the high dimensional space,

that we then truncates. we then project the initial dataset onto the principal directions in the latent space

In the physical space (the plot is interactive, feel free to explore the 3D dataset !)

colors = plt.cm.viridis(np.linspace(0, 1, len(X[0,:]))) # Generate a color gradient

import plotly.graph_objects as go

# colors_plotly = colors[:, :3]

colors_plotly = np.linspace(0, 1, X.shape[1])

x_points = X[0, :]

y_points = X[1, :]

z_points = X[2, :]

# Create the 3D scatter plot

fig = go.Figure(data=[go.Scatter3d(

x=x_points,

y=y_points,

z=z_points,

mode='markers',

marker=dict(

size=5, # Size of the markers

color=colors_plotly, # Color of the markers

colorscale='viridis', # Color scale

showscale=True, # Show color scale

)

)])

fig.update_layout(

scene=dict(

xaxis_title='x',

yaxis_title='y',

zaxis_title='z',

),

title='Physical Space'

)

fig.show()In the latent space

We can see that for linear data, the kPCA behaves similarly to the SVD.